My recollection of The Great Gatsby is that it is full of dancing, but on rereading I find there are only three or four mentions of dancing. This is probably due to the amazing writing of F. Scott Fitzgerald. His description of Gatsby's parties is every bit as evocative and enduring as Charles Dickens' description of Fezziwig's parties. There is an underlying difference, of course. Fezziwig is perfectly comfortable in his community and in his role as host. His parties are a symbol of kindness and good feeling. Jay Gatsby is a self-invented man and he is not comfortable. He is obsessed with Daisy, the girl with whom he fell in love years before. He was a young officer and she was a society girl when they met, but now he is a millionaire and she is married to anther. Gatsby holds parties to try to lure Daisy to him.

His parties are bigger and grander than you would have found in the world of society parties where he first met her, but his parties are also missing the community that her society parties had. Without a community of people with shared values (and similar economic status), Gatsby's parties are a place without rules. That is why they attract show business types and pretenders as well as society folk. It's also why they seem so magical and serendipitous to outsiders. Oh, if only Gatsby could bring himself to fall in love with a chorus girl, the story might not end in tragedy....

His parties are bigger and grander than you would have found in the world of society parties where he first met her, but his parties are also missing the community that her society parties had. Without a community of people with shared values (and similar economic status), Gatsby's parties are a place without rules. That is why they attract show business types and pretenders as well as society folk. It's also why they seem so magical and serendipitous to outsiders. Oh, if only Gatsby could bring himself to fall in love with a chorus girl, the story might not end in tragedy....

There was music from my neighbor's house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars. At high tide in the afternoon I watched his guests diving from the tower of his raft or taking the sun on the hot sand of his beach while his two motor-boats slit the waters of the Sound, drawing aquaplanes over cataracts of foam. On week-ends his Rolls-Royce became an omnibus, bearing parties to and from the city, between nine in the morning and long past midnight, while his station wagon scampered like a brisk yellow bug to meet all trains. And on Mondays eight servants including an extra gardener toiled all day with mops and scrubbing-brushes and hammers and garden-shears, repairing the ravages of the night before. Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York--every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves. There was a machine in the kitchen which could extract the juice of two hundred oranges in half an hour, if a little button was pressed two hundred times by a butler's thumb.

At least once a fortnight a corps of caterers came down with several hundred feet of canvas and enough colored lights to make a Christmas tree of Gatsby's enormous garden. On buffet tables, garnished with glistening hors-d'oeuvre, spiced baked hams crowded against salads of harlequin designs and pastry pigs and turkeys bewitched to a dark gold. In the main hall a bar with a real brass rail was set up, and stocked with gins and liquors and with cordials so long forgotten that most of his female guests were too young to know one from another. By seven o'clock the orchestra has arrived--no thin five-piece affair but a whole pitful of oboes and trombones and saxophones and viols and cornets and piccolos and low and high drums. The last swimmers have come in from the beach now and are dressing upstairs; the cars from New York are parked five deep in the drive, and already the halls and salons and verandas are gaudy with primary colors and hair shorn in strange new ways and shawls beyond the dreams of Castile. The bar is in full swing and floating rounds of cocktails permeate the garden outside until the air is alive with chatter and laughter and casual innuendo and introductions forgotten on the spot and enthusiastic meetings between women who never knew each other's names.

The lights grow brighter as the earth lurches away from the sun and now the orchestra is playing yellow cocktail music and the opera of voices pitches a key higher. Laughter is easier, minute by minute, spilled with prodigality, tipped out at a cheerful word. The groups change more swiftly, swell with new arrivals, dissolve and form in the same breath--already there are wanderers, confident girls who weave here and there among the stouter and more stable, become for a sharp, joyous moment the center of a group and then excited with triumph glide on through the sea-change of faces and voices and color under the constantly changing light. Suddenly one of these gypsies in trembling opal, seizes a cocktail out of the air, dumps it down for courage and moving her hands like Frisco dances out alone on the canvas platform. A momentary hush; the orchestra leader varies his rhythm obligingly for her and there is a burst of chatter as the erroneous news goes around that she is Gilda Gray's understudy from the "Follies." The party has begun. (F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 1925.

|

| Gilda Gray |

The workers lay canvas to make a dance floor outside. It sounds much nicer than dancing on grass or gravel. The music is very up to date, and jazzy, with lots of wind instruments.This is the era of Prohibition, but it is only illegal to sell alcohol, not to drink it. Prohibition began January 1920, but there had been a temporary wartime prohibition on strong alcohol since November 1918, so by 1923 (the probable date for the events in the book) there would be a crop of young women who had no recollection of the names of various cordials, and also little remembrance of people drinking in moderation.

The young woman who is first to dance is not the understudy of Gilda Gray, but by bringing up that name, Fitzgerald's audience would be clued in to exactly what kind of dance she is doing.

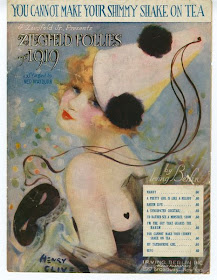

Gilda Gray was popularly credited with inventing the Shimmy. Of course, Bee Palmer was also credited with inventing the same dance. In both cases it was a matter of an attractive young woman shaking her shoulders until her entire body wiggled. It seems to be a precursor to the Charleston, and even makes the Charleston look a bit refined. From the sheet music, it looks like the Shimmy was most popular in 1919.

|

| You Cannot Shake that "Shimmie" Here (but maybe you can at Gatsby's!) 1919 |

|

| Gilda Gray |

|

| Bee Palmer, I Want to Shimmie, 1919 |

No comments:

Post a Comment